The Colombian Conflict: Peace Eludes a Fractured Nation

Despite peace efforts, Colombia’s fractured past continues to shape its future. The second in a three-part series.

In our first piece, we traced the roots of Colombia's decades-long conflict, examining how inequality, entrenched ideologies, and the actions of guerrilla groups, paramilitaries, and the State created a relentless cycle of violence. Failed peace attempts normalised armed conflict as a political tool, embedding violence deep within the nation’s fabric.

By the early 2000s, the weakening of the FARC (Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia) and a growing public outcry against violence paved the way for a new approach, culminating in the 2016 peace agreement.

Yet the echoes of war remain deafening. Car bombs still shake military bases, businesses and shopkeepers live under constant extortion threats, and armed groups enforce lockdowns at gunpoint in vast, lawless regions. On the radio, anguished voices in the middle of the night beg for answers about the kidnapped and disappeared—haunting reminders of Colombia’s unresolved trauma.

What began as a battle of ideologies has transformed into a fragmented struggle for power, profit, and control. While some old actors like the ELN endure, others have splintered and reconfigured, seizing opportunities in an evolving conflict.

In this second part, we examine the forces sustaining Colombia's violence today and the monumental challenges on its path to lasting peace.

If you missed our first part, read it here:

The road to the 2016 peace agreement

Santos Seizes the Opportunity

The election of President Juan Manuel Santos in 2010 marked a turning point for Colombia’s peace prospects. Building on the weakened state of the FARC after years of military operations and public frustration with deteriorating security, Santos opened dialogue with illegal armed groups. His approach signalled a critical shift: military solutions alone would no longer suffice.

Plan Colombia: A Controversial Legacy

Plan Colombia, launched in 2000 with US$12 billion in U.S. aid, aimed to address drug trafficking, guerrilla violence, and institutional weaknesses. Initially designed as a development program, it morphed into a militarised strategy focused on counter-narcotics, especially after 9/11, aligning more with U.S. priorities than Colombia’s needs.

Key Achievements:

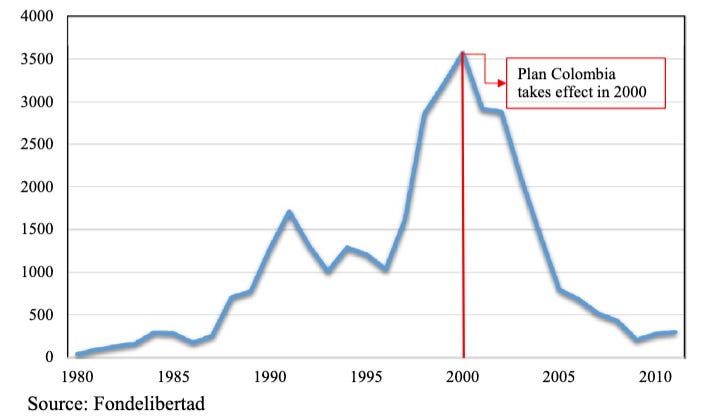

Kidnappings fell from 3,500 in 2002 to around 200 by 2009 (Fig. 1).

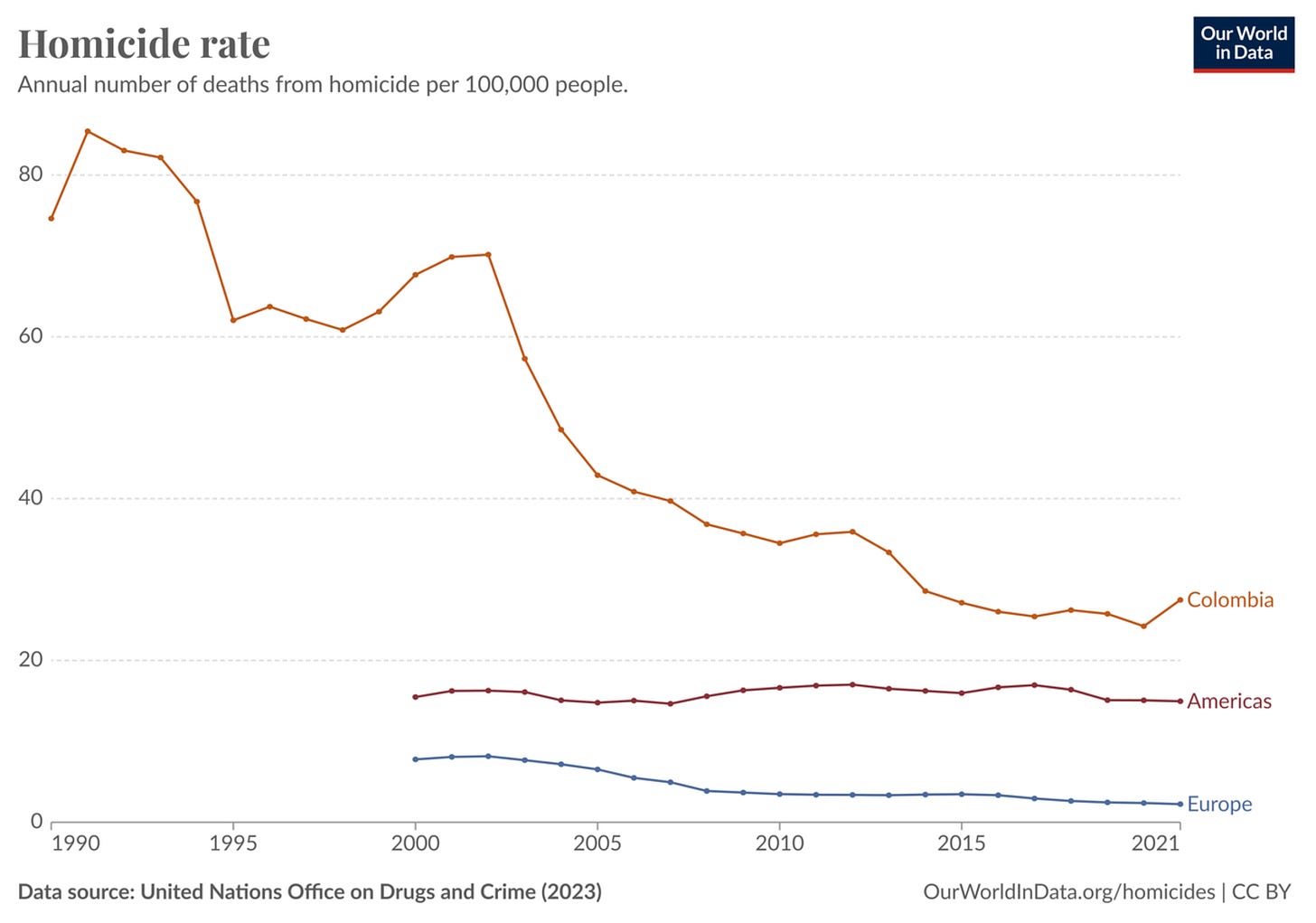

Homicides dropped by half, and the FARC’s forces shrank by nearly 50%.

The Hidden Costs:

While these gains were significant, they came at the expense of rural development and human rights. Forced displacement surged, leaving rural communities vulnerable to violence and neglect.

Displacement and Dispossession: the Invisible Crisis

Colombia hosts the largest displaced population in the world, with rural families uprooted by land seizures, threats, and atrocities. Armed groups, funded by drug trafficking and extortion, impose heavy taxes on campesinos, driving them from their land.

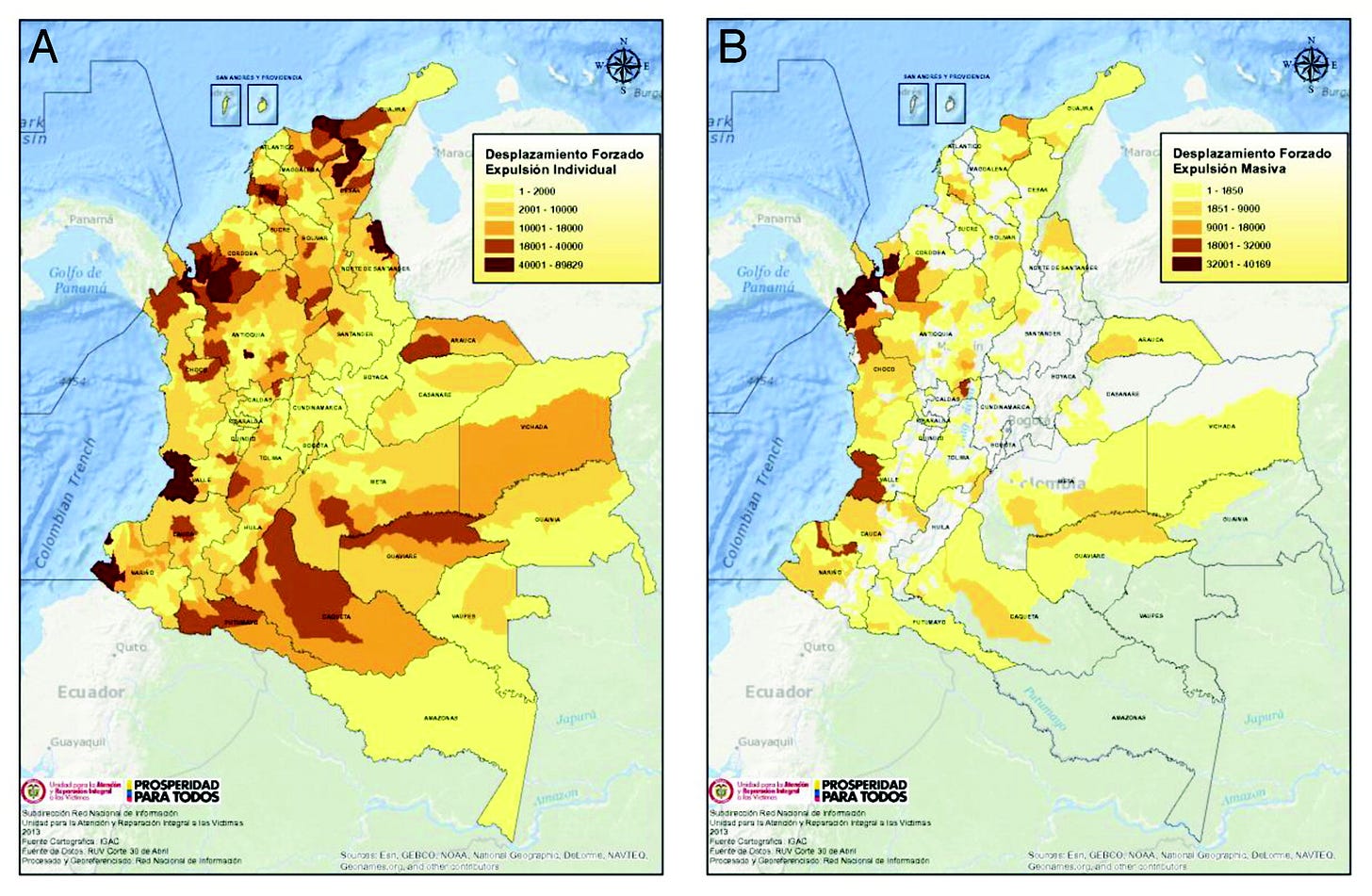

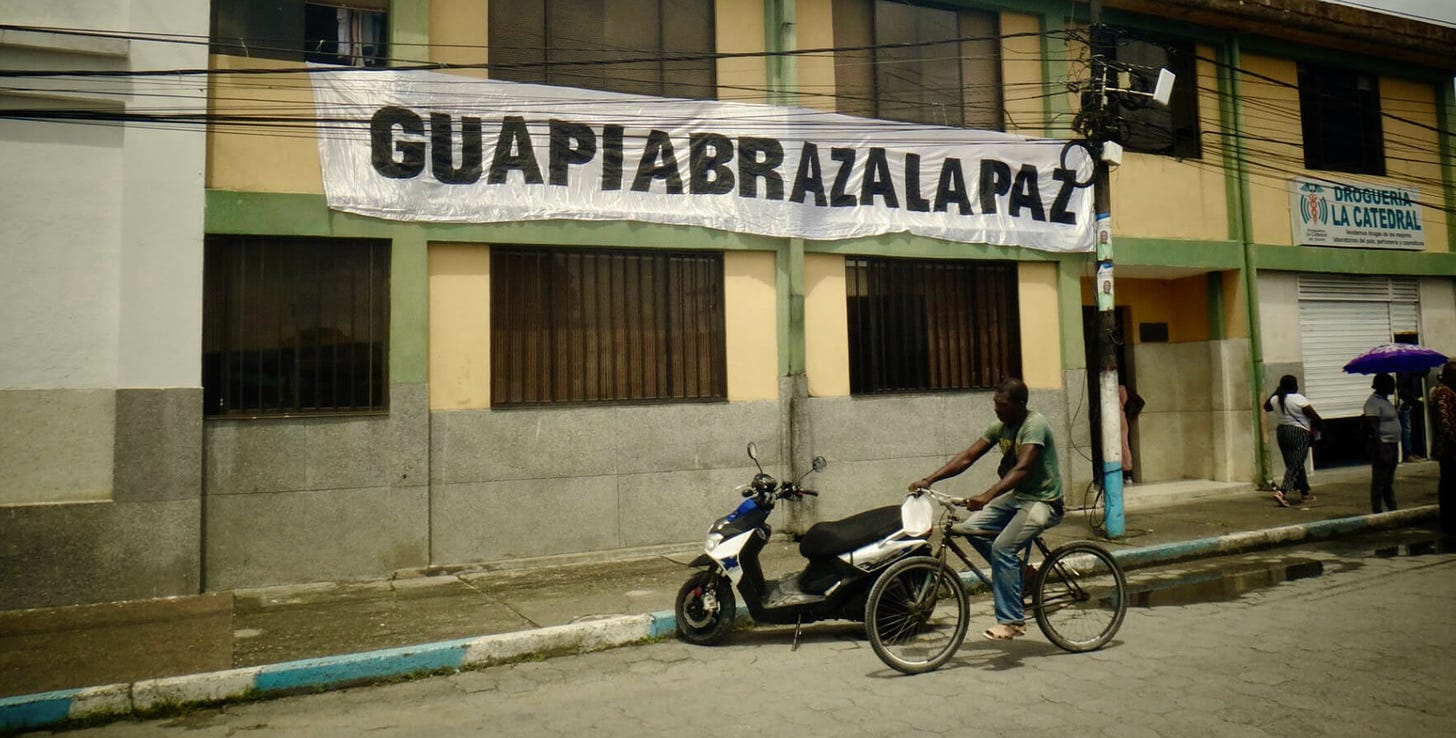

92% of displacements occur in rural areas, disproportionately affecting ethnic minorities such as Afro-Colombians and Indigenous peoples (Fig. 2).

Mass displacements regularly devastate entire communities, particularly along the Pacific coast.

Ethnic minorities are overly represented among those displaced.

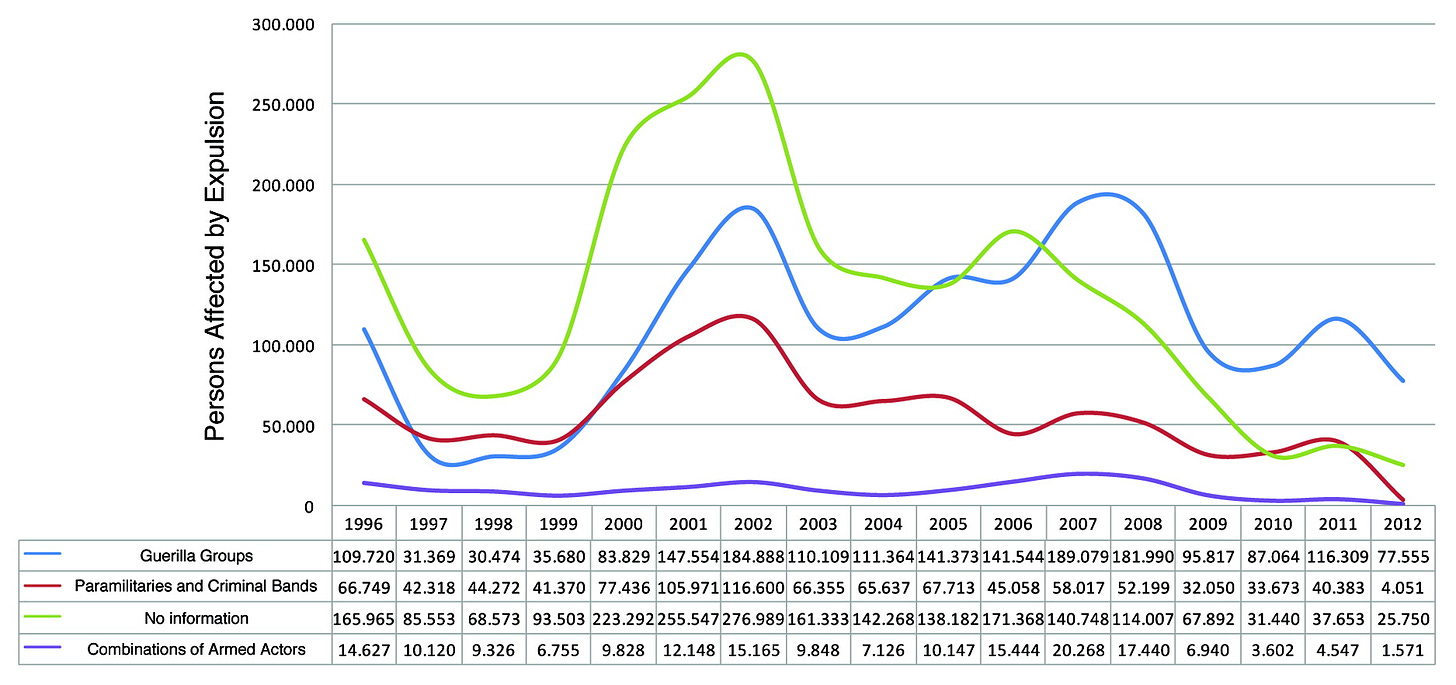

Colombia’s internal displacement crisis stems from an armed conflict fuelled by illegal activities such as drug trafficking, extortion, and resource exploitation (Fig. 3). Armed groups impose harsh taxes on campesinos, driving families from their lands and worsening rural insecurity.

Yet, the narrative of forced displacement is neither widely publicised nor broadly disseminated throughout the media and the international community.

Why Is This Crisis Overlooked?

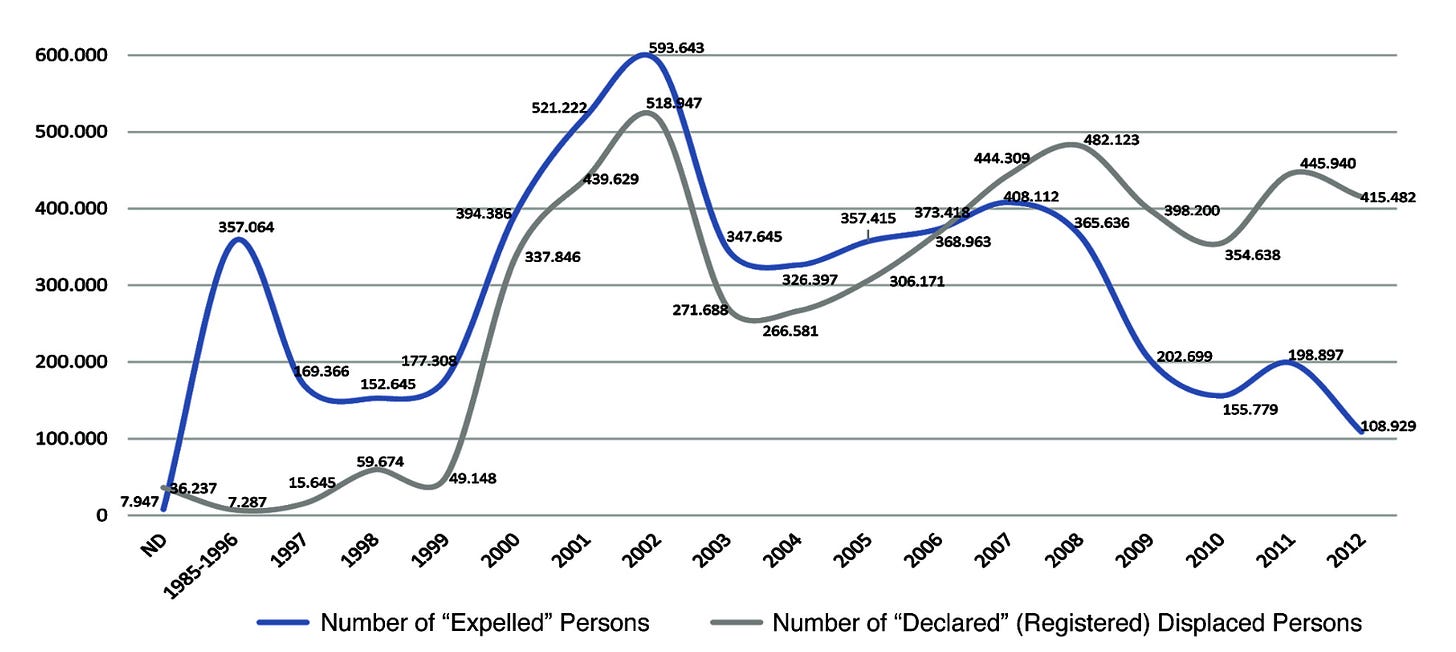

Despite its staggering scale (Fig. 4), the narrative of forced displacement is neither widely publicised nor broadly disseminated. Perhaps because internal displacement in Colombia has been a long-term reality, rather than a war-led, breaking news story —as in the case in countries such as in Syria, Iraq, Sudan and other war-torn countries.

Falling Short in Rural Security

While military operations cleared the guerillas, they failed to establish lasting government control or provide essential services in rural regions. Meanwhile, guerillas would relocate to other parts of the country, rather be permanently defeated. The plan did not provide viable economic alternatives to the continued growth of drug trafficking and illegal mining.

False Positives Scandal:

The intense pressure to deliver military victories led to the killing of 6,402 civilians, deliberately and falsely reported as guerrilla combatants, between 2002 and 2008 during President Álvaro Uribe’s presidency. This scandal deepened public distrust in state institutions.

While Plan Colombia achieved measurable gains in security, its militarised approach left deep scars in rural communities and unresolved structural issues.

Can Colombia truly break free from cycles of violence without addressing the social and economic inequalities that perpetuate the conflict?

Public Outcry and the Turning Point

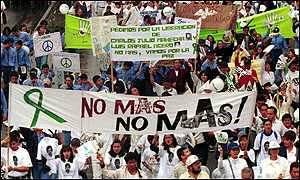

By 1999, despair over worsening violence had pushed millions to act. On October 24, between 5 and 10 million Colombians marched in a historic “No más” protest, demanding an end to kidnappings, atrocities, and war.

For many, emigration was the only option—700,000 citizens left Colombia between 1995 and 2000, according to Colombia’s DANE agency.

Negotiations Begin

Amid this backdrop, Santos prioritised peace talks with the FARC. By 2010, the group’s diminished strength made negotiations viable for both sides. After decades of failed attempts, four years of talks culminated in the landmark 2016 peace agreement, raising hopes for a lasting resolution to Colombia’s violent history.

A ground breaking agreement

Addressing the Root Causes

The 2016 peace accord was groundbreaking because it went beyond ending violence, aiming to tackle the conflict's underlying causes. It committed both sides to:

Ending violence permanently.

Establishing transitional justice (JEP) to ensure accountability and restorative justice for victims.

Investing in rural development and rebuilding neglected FARC-controlled regions.

Expanding political representation.

Replacing illicit coca crops with legal alternatives to curb the drug trade.

While over 14,000 ex-FARC combatants disarmed, the agreement’s implementation has been painstakingly slow due to bureaucracy and political resistance, especially under Iván Duque, a staunch opponent of the deal.

A Long Road to Peace

Peace takes time to achieve. The accord's 15-year timeline reflects the complexity of the changes needed.

Yet, the Kroc Institute reports that as of May 2024, only 33% of the peace accord's stipulations have been fully implemented, with 37% seeing minimal progress. At this pace, the agreement may fall short of its 2031 deadline. . By May 2024, only 33% of the stipulations had been fully implemented, and 37% showed minimal progress. At this pace, the agreement risks falling short of its 2031 target.

Violence Adapts, Not Ends

Peace is not simply the absence of armed groups. The FARC’s demobilisation created power vacuums now filled by dissidents and criminal organisations, reigniting violence in many areas.

Localised Conflicts:

While Colombia’s homicide rate has stabilised at around 25 per 100,000 people—far below the 1990s peak of 80—it remains among the highest in South America behind the neighbouring countries of Ecuador and Venezuela.

Violence is concentrated in:

The department of Putumayo on Colombia’s border with Ecuador (60.6 per 100,000): A hotbed for ex-FARC confrontations.

Cauca (53.3 per 100,000): A major site of drug trade violence.

San Andrés y Providencia (65.8 per 100,000): An emerging migrant smuggling route.

Dissidents and new armed groups now prioritise financial gain over ideology, dominating drug trafficking, illegal mining, and extortion. These evolving dynamics reflect a shift from national insurgencies to localised, profit-driven conflicts.

Unfinished Business

The 2016 peace agreement was a historic step forward but remains incomplete. With slow progress and persistent violence, critical questions loom:

Can Colombia overcome its political divides and fragile institutions to achieve the transformative change it desperately needs?

Dissidents, Drugs, and Dystopia: A New Face of Violence

Unfulfilled Promises Breed New Threats

The slow implementation of the 2016 peace agreement, particularly on land reform and political participation, has left many former FARC members dissatisfied. This discontent has fuelled the rise of dissident factions, including the Estado Mayor Central (EMC) and Segunda Marquetalia, which now drive new waves of violence and instability.

Emerging Actors in Colombia’s Conflict

FARC Dissident Groups:

Estado Mayor Central (EMC): Has “significant armed power that allows it to maintain control of different criminal rents across the country” (InsightCrime). Its criminal portfolio mostly revolves around drug trafficking in the south of the country, illegal mining, and extortion. It is fostering deforestation and land appropriation to control cattle ranching activities, particularly in the Amazon basin departments of Meta, Caquetá and Guaviare (ACLED).

Segunda Marquetalia: Operates mainly in the mountainous regions along the Colombia-Venezuela border, it concentrates on cocaine trafficking, reportedly benefiting from Venezuela’s tacit approval. While its influence is expanding, it has not reclaimed the FARC's former strongholds.

ELN:

Now Colombia’s most prominent guerrilla group, the ELN operates in former FARC territories, with a significant presence in Venezuela. It relies heavily on ransom kidnappings, especially in oil-rich regions like Norte de Santander and Arauca.Paramilitary Successors (BACRIM):

Also known as “criminal bands” or “BACRIM” (for bandas criminales), criminal groups that emerged from former paramilitary structures include the Clan del Golfo which filled the void that followed the FARC’s disarmament and fed off ongoing government neglect in rural areas. It dominates 60% of Colombia’s cocaine trade and operates across 30% of the country, controling coca paste production and trafficking routes, leveraging its territorial strongholds for drug smuggling and other criminal activities.Its model is based on “local cells that are financially self-sufficient”. Some cells have moved into criminal economies outside of drug trafficking, such as illegal mining, extortion, migrant smuggling, and micro-trafficking.

It has also taken advantage of its presence in northern Colombia to become a gatekeeper of the Darién Gap, a once impenetrable jungle connecting Colombia and Panamá, crossed by over 520,000 migrants in 2023 on their way to Mexico and the United States. International Crisis Group estimates the Clan earns between US$50 and US$80 per migrant crossing the Darién. It also dictates which precise route migrants can use on a given day to keep them away from cocaine shipments.

Urban Gangs:

In cities like Buenaventura and Medellín, local gangs have risen to power, battling for territorial control and engaging in violent criminal enterprises.

From Ideology to Opportunism

Unlike the pre-2016 conflict, today’s armed groups prioritise economic gain over ideology. Their motivations include:

Financial profit through drug trafficking, illegal economies, and extortion.

Territorial control to dominate local economies and enforce authority over populations.

Opposition to the peace process, targeting ex-combatants in reintegration programs as threats or traitors.

While some dissident groups retain FARC-era rhetoric, it serves more as a façade for legitimacy than a commitment to ideological goals.

A Fragmented Conflict

Colombia’s conflict has devolved into a fragmented, decentralised struggle for profit and control. The rise of dissidents and criminal networks poses new challenges for the state.

Key Questions:

Can Colombia counter these evolving threats while rebuilding trust and restoring governance in neglected regions?

Will this evolution make peace more elusive, or could a focus on local solutions pave the way for lasting stability?

Conclusions

A Fragile Peace

Peace in Colombia remains precarious. The 2016 agreement marked a historic attempt to end decades of violence, but the conflict has shifted. Economic interests and localised power struggles have replaced ideological battles, fragmenting the conflict and complicating pathways to peace.

Drivers of Continued Violence

Contemporary armed groups vie for control over Colombia’s lucrative illegal economies, particularly drug trafficking routes. These criminal enterprises fuel ongoing instability and hinder efforts to establish lasting security, even as the government grapples with implementing peace agreement provisions.

Petro’s Controversial Gamble

President Gustavo Petro has staked much of his political capital on negotiating with armed groups to bring Colombia’s conflict to an end. His approach is bold but divisive. With only 18 months left in his term, the clock is ticking: can Petro achieve a breakthrough before political pressures and time run out?

Looking Ahead

In the final part of this series, we assess the state of Colombia’s peace efforts and explore the challenges and opportunities shaping its future.

Is lasting peace within reach, or will Colombia remain trapped in cycles of violence?

Subscribe (for free) and don’t miss our final post in the series.