🔎 Can Colombia Find Lasting Peace?

Eight years after the 2016 FARC peace accord, what are the chances of lasting peace in Colombia? The first in a three-part series.

Eight years ago, Colombia and the world celebrated the signing of a historic peace accord between the government and the FARC, the country’s largest guerrilla group. Yet today, the question remains: has peace truly taken hold? Despite the promises of the 2016 agreement, violence persists, and the scars of a conflict that claimed over 450,000 lives are far from healed.

From the shadow of the infamous Banana Massacre to the rise of guerrilla warfare and drug cartels, Colombia’s struggles reveal a history steeped in inequality, power struggles, and shattered dreams.

In this three-part series, we explore the roots of Colombia’s conflict and ask: what will it take for the nation to finally break free from its cycle of violence?

The Roots of the Colombian Conflict: Steeped in Inequality

For many, the Colombian conflict is synonymous with the drug trade, epitomized by the infamous Pablo Escobar and the Medellín Cartel. However, the roots of this conflict run far deeper, rooted in centuries of social and economic inequality.

The United Fruit Company and the Banana Massacre

The conflict’s origins can be traced back to 1928, when workers on banana plantations owned by the United Fruit Company (now Chiquita Brands International) demanded better working conditions. The company, a powerful economic force, controlled vast tracts of land and wielded significant political influence, often to the detriment of local communities.

When workers went on strike, the Colombian military brutally suppressed the protests in what became known as the Banana Massacre. While official estimates recorded 68 deaths, some claim the toll was as high as 2,000. This violence highlighted the deep inequalities and government collusion with foreign corporations, fueling resentment in rural areas and laying the groundwork for leftist revolutionary movements.

When the Banana Company arrives in Macondo, the jungle town in Gabriel García Márquez’s “One Hundred Years of Solitude,” it brings with it first modernity and then doom. “Endowed with means that had been reserved for Divine Providence in former times,” García Márquez writes, the company “changed the pattern of the rains, accelerated the cycle of harvests and moved the river from where it had always been.” It imported “dictatorial foreigners” and “hired assassins with machetes” to run the town; it unleashed a “wave of bullets” on striking workers in the plaza. When the Banana Company leaves, Macondo is “in ruins.”

Daniel Kurtz-Phelan, New York Times, 2/03/2008

This context promoted the creation of leftist and revolutionary organisations. Long-standing grievances over land distribution and political exclusion intensified by foreign corporate interests set the stage for what became known as the Colombian conflict.

La Violencia: Armed Struggle Becomes the Norm

The assassination of Jorge Eliécer Gaitán, a popular Liberal politician, in 1948 sparked riots known as the Bogotazo, escalating into a decade-long civil war known as La Violencia. This conflict, which left 200,000 dead and displaced countless others, normalised violence as a means of resolving political disputes.

La Violencia laid the groundwork for the Colombian conflict by creating deep-seated political and social divisions. Political polarisation, exacerbated by the failure to address underlying socio-economic inequalities, contributed to the rise of guerrilla movements

In its aftermath, guerrilla movements such as the FARC and ELN emerged, rooted in calls for land reform and social justice—issues that had gone unaddressed during La Violencia.

An Unequal Nation

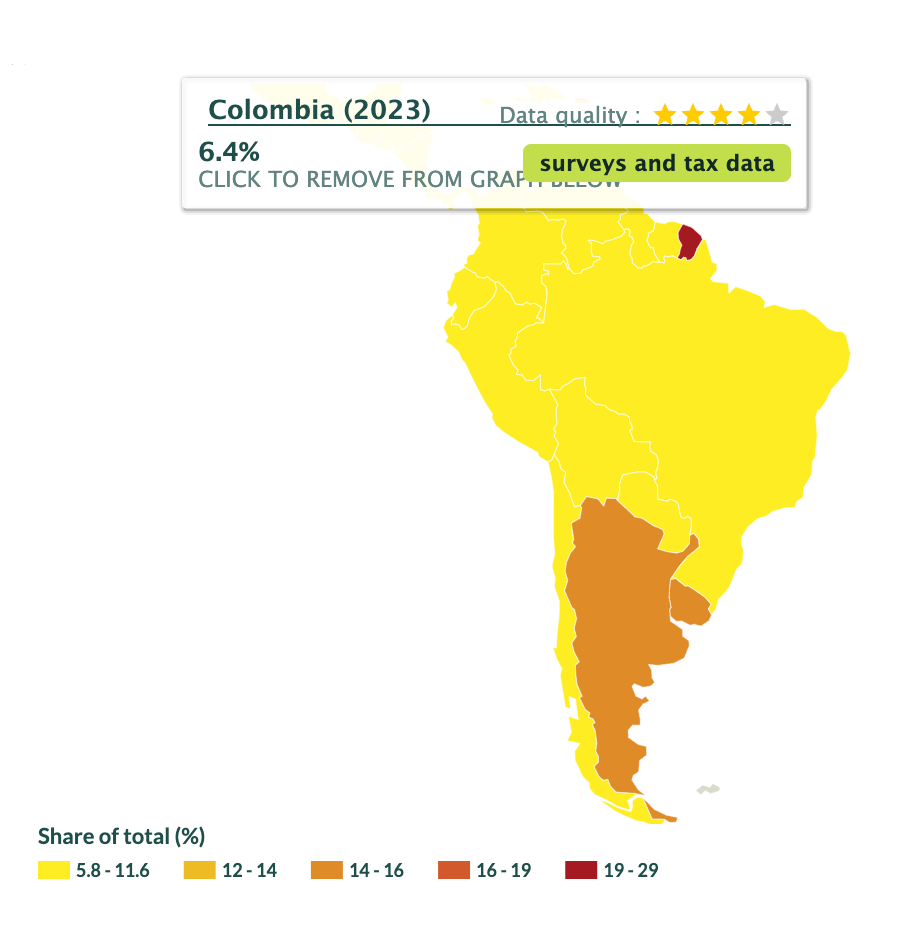

Despite its natural wealth, Colombia remains one of the most unequal countries in the world.

The bottom 50% of the population owns just 6.4% of the national income — one of the smallest in the world (Figure 1).

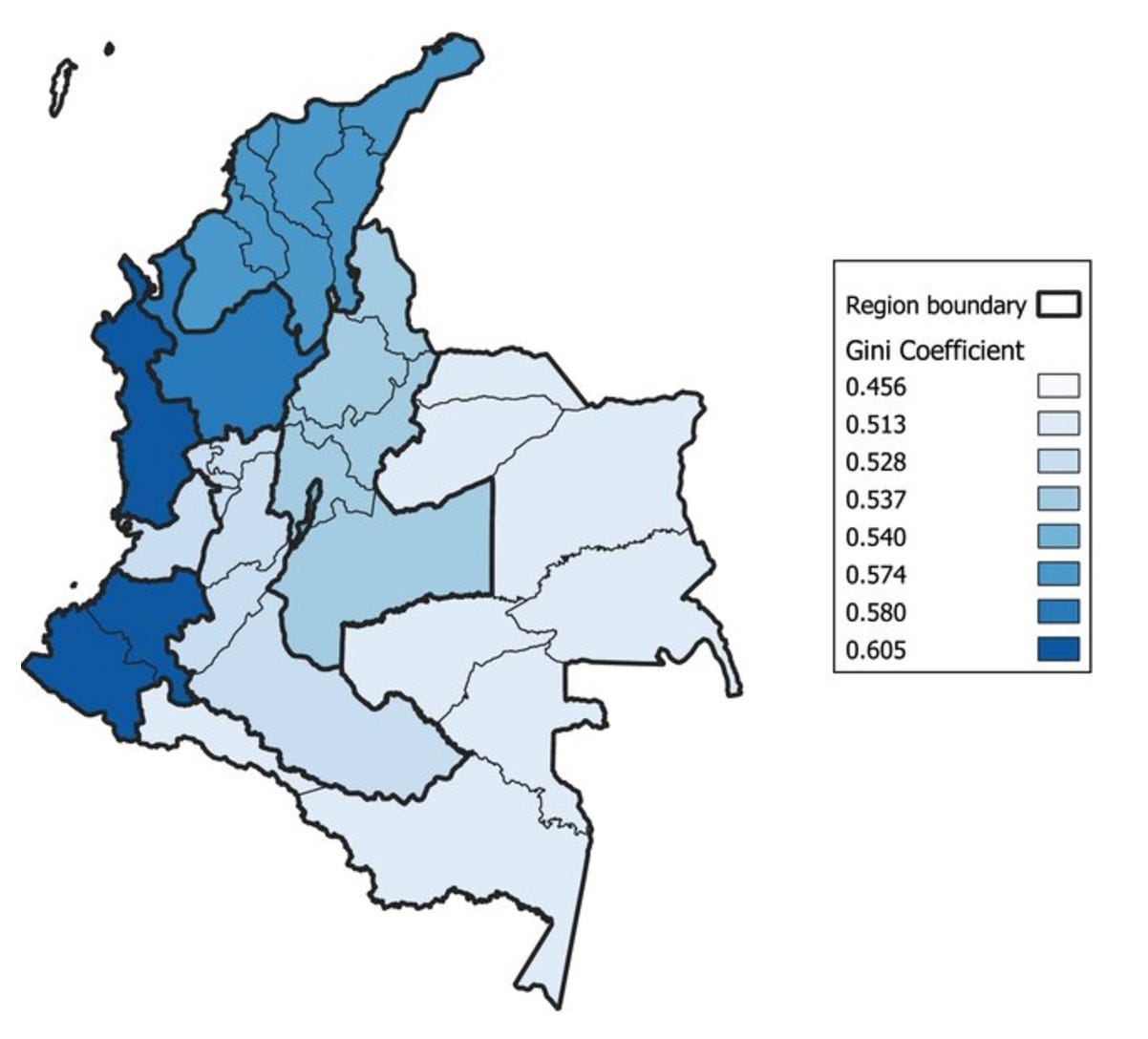

Whilst 30 percent of Colombians live below the poverty line in urban Colombia, this proportion more than doubles in rural regions. Poverty is particularly stark in rural regions, where inequality fuels resentment and provides fertile ground for armed groups. The departments of Chocó, Nariño, and Cauca are among the most unequal and impoverished regions in the country (Figure 2), exacerbating tensions between rural communities and the state.

From Ideology to Opportunism

Colombia’s Truth Commission estimates that the conflict has resulted in 450,000 deaths, with countless more kidnapped, displaced, or disappeared. Initially ideology-driven, the conflict evolved into a struggle for power and financial gain, fuelled by illicit economies like drug trafficking and illegal mining. It involved a variety of actors.

Guerrilla Groups

The FARC and ELN started as Marxist-Leninist movements but later relied heavily on profits from drugs and kidnappings.

The FARC, officially known as Fuerzas Armadas Revolucionarias de Colombia - Ejército del Pueblo were founded in 1964 as the military wing of the Colombian Communist Party and operated under a Marxist-Leninist ideology. It sought to overthrow the Colombian government and implement socialist reforms. It was the largest and most influential guerrilla group until its demobilisation following the 2016 peace agreement.

They were not the only guerilla in town. Also founded in 1964, the Ejército de Liberación Nacional (ELN, or National Liberation Army) has been one of the oldest guerrilla groups in Colombia. Its actions were initially driven by its Marxist-Leninist ideology, focusing on issues of social justice and anti-imperialism. It remains active today. It continues to engage in armed conflict, primarily funded by drug trafficking and kidnapping.

Other guerillas included the Maoist People’s Liberation Army (EPL), and M-19. The roots of their armed campaign lied in La Violencia. Communist guerrilla groups were excluded from the power-sharing agreement which ended the violence, and so they took up arms against the new unified government.

To finance their activities, the guerilla groups initially relied mostly on extortion of local communities and kidnappings of businessmen and land owners.

Over time, however, they increasingly benefited from illicit economies such as drug trafficking and illegal mining.

Paramilitary groups

Opposing leftist guerillas were right-wing paramilitaries, particularly the Autodefensas Unidas de Colombia (AUC) and the Gaitanist Self-Defense Forces of Colombia, today referred to as the Clan del Golfo (or Clan).

The Clan emerged from former paramilitary structures and is today heavily involved in drug trafficking.

Operating on an anti-communist agenda, paramilitaries fought the guerillas. They often justified their actions as necessary for defending rural landowners and local communities from guerrilla violence and extortion.

From the outset the paramilitaries enjoyed deep rooted support from the Colombian state. Human Rights Watch at the time published a report on the paramilitaries in Colombia. It was titled “The Sixth Division: Military-Paramilitary Ties and U.S. Policy in Colombia” — a reference to the Colombian army which only has only five divisions.

The "Sixth Division" is a phrase used in Colombia to refer to paramilitary groups. Colombia's Army has five divisions, but many Colombians told Human Rights Watch that paramilitaries are so fully integrated into the army's battle strategy, coordinated with its soldiers in the field, and linked to government units via intelligence, supplies, radios, weapons, cash, and common purpose that they effectively constitute a sixth division of the army.

Human Rights Watch, 2008

Operating with the complicity of the Colombian State, the paramilitaries targeted much of their violence against political activists.

They were notorious for their brutal tactics, including massacres, forced disappearances, and targeted killings of social leaders, trade unionists, and civilians suspected guerrilla sympathisers — President Álvaro Uribe, elected in 2002 with the blessing of the paramilitaries, had promised to take a hard-line approach against the guerrillas. Many of Uribe’s closest allies – including his brother, cousin and personal secretary – have been “jailed or have been under investigation for their role in human rights abuses” said Justice for Colombia.

The paramilitaries were named by Colombia’s Truth Commission as the main perpetrators of the killings, responsible for approximately 45 percent of the 450,000 dead (most of whom were civilians) and 52 percent of the 110,000 victims of forced disappearances.

Many paramilitary groups began demobilising in 2003 under a government initiative known as the Justice and Peace Law aimed at “demobilising the various paramilitary groups that have grown economically and politically powerful through the lucrative drugs trade and that are responsible for decades of violence”.

This process, criticised for its leniency on perpetrators of human rights violations, led to the disarmament of over 30,000 combatants —but it left many mid-level commanders and factions active, which later evolved into new criminal organisations.

Government forces

Government forces also played a part — for what they’ve done and what they haven’t.

State Absence and the Rise of Armed Groups

Let’s start with what the State hasn’t done - exercise its presence and authority in vulnerable territories. The weakness of the Colombian State in rural territories has provided armed groups with the political opportunity for rebellion, as most rebel consolidation took place in areas of Colombia that lacked a strong State presence. The growth of Colombia's armed groups has been closely linked to their ability to loot exportable natural resource commodities. Rural territories have been neglected by successive governments, to the point that some are today controlled by criminal organisations.

But government forces have also committed atrocious crimes.

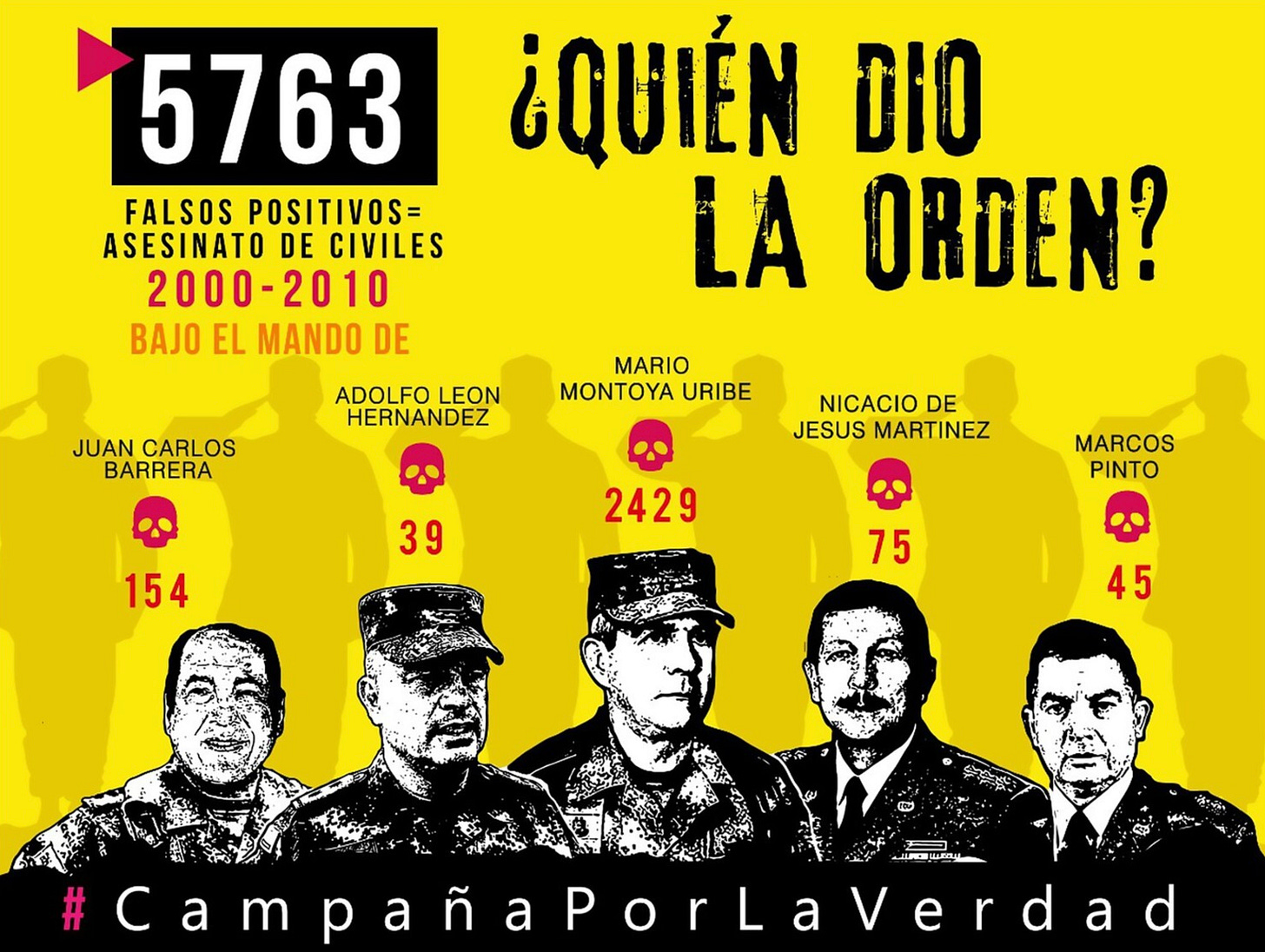

Collusion and the ‘False Positives’ Scandal

The Colombian military and the police have been central actors in combating both guerrilla and paramilitary groups. By colluding with the paramilitaries, and by fighting against the guerillas, they too have been accused of human rights violations, including extrajudicial killings during operations against these groups. More than 11,000 individuals have been implicated in the collusion, including around one-third of the members of the 2006-10 Senate and hundreds of mayors and regional politicians.

And horrendous is the involvement of state forces in the murder of more than 6,402 innocent people to boost war figures and claim rewards. This was known as the false positives scandal – the killing of civilians by army or state forces which are then presented as the deaths of guerrilla combatants.

“The sheer number of cases, their geographic spread, and the diversity of military units implicated indicate these killings were carried out in a more or less systematic fashion by significant elements within the military”.

Prof Philip Alston, UN Special Rapporteur on Extrajudicial Executions

Conclusion: A Fragile Peace

The involvement of guerrilla groups, paramilitaries, and state forces created a web of violence that persists despite peace efforts. The 2016 accord was a milestone, but long-standing inequalities, state absence in rural areas, and economic incentives for armed actors to continue fighting have jeopardized its success.

Next Week

In Part Two, we’ll examine the reconfiguration of criminal groups after the 2016 peace agreement, the shift from ideology to opportunism, and President Petro’s efforts to secure “total peace” in Colombia.