Why is Latin America the World's Most Violent Region?

An apparently simple question, calling for complex answers. By Prof. Nicolas Forsans

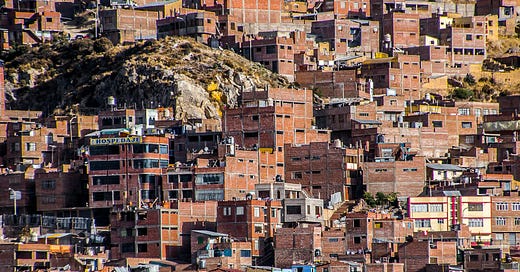

Latin America is home to some of the world's most beautiful landscapes and vibrant cultures, but it also carries the unfortunate title of being the most violent region on Earth. With only 8% of the global population, the region accounts for a staggering one-third of the world’s homicides. But why? What drives the unprecedented levels of violence that ravage countries from the Caribbean to the Southern Cone? This post digs into the complex web of factors—historical, economic, social, and political—that fuel the violence in Latin America, challenging the simple answers and uncovering the deeply rooted causes that continue to plague the region today.

It is simple question. yet the answer is incredibly complex.